Section 2

Samira: We are now in the Reading Room of Asia Art Archive’s library. At the centre of this space are the blown-up versions of Mukherjee’s installation instructions made between 1986 and 1992. Facing the contact sheets are the installation instructions for Pari , the artwork at the entrance of our library. I invite you to come closer to the image, and read the text and measurements. The folds and knots of the artwork have been measured to the centimetre. Every detail is accounted for, such as instructions to remove the packing and labels.

On the two other sides of this pillar are installation instructions that were created by Mukherjee’s then-husband Ranjit Singh, who was an architect. These were made on her direction, and were used when Mukherjee’s work started traveling extensively, as she was unable to be present to install her works each time. In the rack behind the pillar, you’ll find an interactive screen where you can browse all the installation instructions from the archive.

These instructions are particularly interesting documents because Mukherjee’s work—and she herself has used these terms—is often described as “improvised,” “intuitive,” and “fertile.” However, in these documents you get a strong sense of codification and control instead. For us, this presents a kind of tension with the organicity of the artwork that you saw when you entered, and alters the preconceived notions that we had of Mukherjee’s practice and method, which appear to be in-between the improvised and the measured.

Our title of the exhibition, “mould the wing to match the photograph “ is also taken from an installation instruction to foreground the kind of back-and-forth that takes place between the artwork and the archive.

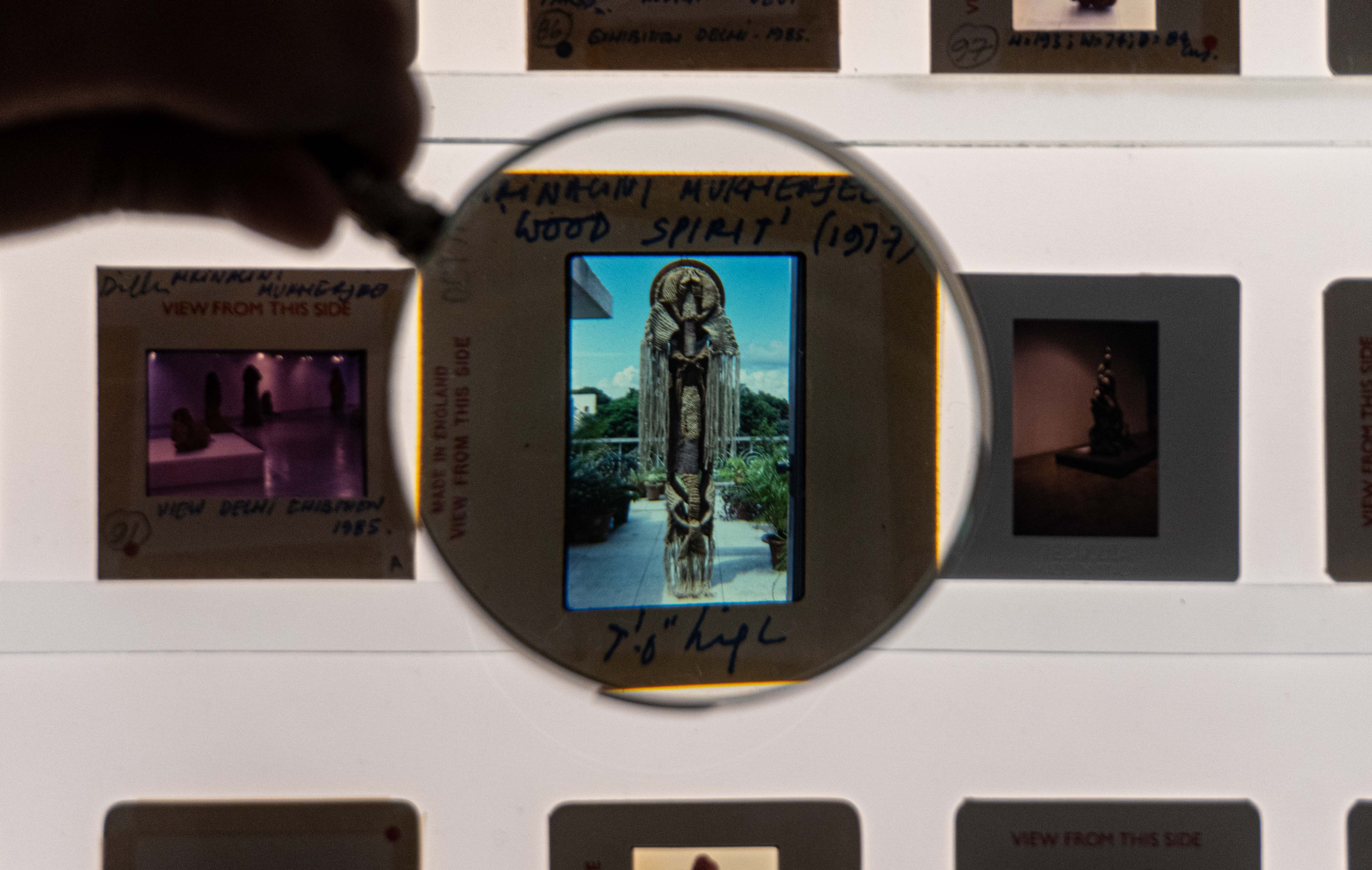

Pallavi: The installation instructions have been magnified for our display. Now I invite you to engage with a very different kind of scale. In Mukherjee’s archive, we discovered thousands of 35mm slides capturing her artworks. Here, on the windows of the library, are the reproductions of hundreds of these slides. I invite you to move the racks, take the slides out, and look at them closely.

When juxtaposed with the sheer scale and grandeur of Mukherjee’s sculptures, these slides provide a microscopic perspective of the creatures she created in her work. It's a captivating contrast to the way her sculptures project majesty and awe, while her archive houses an extensive collection of these tiny positives. The same sculptures that we would look up at are now in our hands in these miniscule slides, and require us to peer at them closely. The archive inverts the experience of the artwork, and provides a kind of intimacy.

Samira: I now invite you to turn around to the other side of the room, where you will see an enlarged photograph. This photo shows Mukherjee with her late friend and prominent artist, Manjit Bawa, and an assistant (whose name we could not locate) testing out the installation of her sculpture “Woman on Swing,” made in 1989. Here, you see the otherwise precious and powerful artwork awkwardly hanging on a tree, with Mukherjee trying to fix it, while her friend laughs as he holds it up. The “improvised” nature of her installation process is made clearly visible, and it provokes a kind of tension with the highly measured installation instructions. Now, let’s walk through the door into the study area, where the tree motif continues.

Image: Installation view of “…and it is something which grows in all directions“ at Project_Space, The Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art, New Delhi, 2022. Photo: Pritish Bali.